For example, the values-and-dimensions approach characteristic of Hofstede (2001), Inglehart and Welzel (2005), and Schwartz (2006) focuses on identifying the values or dimensions along which groups differ, focusing on cultural differences rather than cultural distance.

These approaches are widely used but have various limitations. Within economics and political science, genetic distance and linguistic distance are often used as proxies for cultural distance ( Desmet, Ortuño-Ortín, & Wacziarg, 2017 Gorodnichenko & Roland, 2017 Spolaore & Wacziarg, 2018). Notable examples include Kogut and Singh’s (1988) composite measure of Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions and Demes and Geeraert’s (2014) scale of perceived cultural distance. These difference measures are sometimes combined and used as distance measures. Apart from the many differences identified by cultural psychologists ( Heine, 2015 Henrich et al., 2010), notable attempts to quantify these differences include Hofstede’s (2001) cultural dimensions, Inglehart and Welzel’s (2005) cultural map, and Schwartz’s (2006) values. The measurement of cross-cultural psychological differences and cultural distances has a long history.

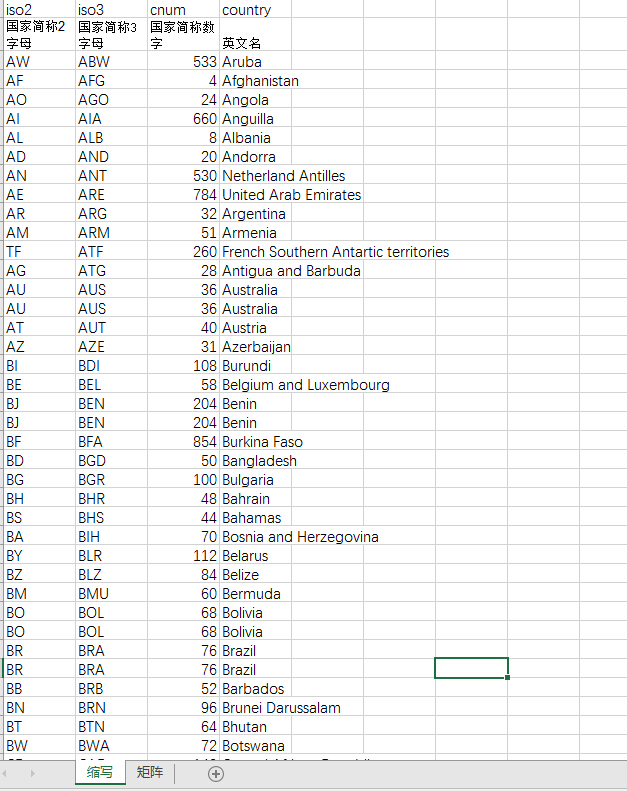

THE GEODIST DATABASE CODE

Using our R code or online tool ( researchers can create scales of cultural distance with any comparison population, which will become increasingly important as the literature becomes less WEIRD. As a point of comparison, we also developed a Chinese scale of cultural distance from China, the largest population on Earth and a common cultural comparison. Because psychological data remain largely American ( Rad et al., 2018), we developed an American scale of cultural distance from the United States as an example. This method allows us to develop scales of cultural distance, and therefore cross-cultural psychological distance, 1 by selecting any population as a point of comparison. Just how psychologically different are the nations of the world compared with each other and with the overscrutinized United States? Many hard drives have been filled with the ways in which China and Japan differ from the United States and Canada, but just how psychologically distant is the culture of China from Japan, the United States from Canada, or Azerbaijan from Zambia? Here, we introduce a robust method for quantifying this distance. A growing body of theoretical and empirical work in cultural evolution emphasizes that our species is fundamentally cultural, and thus, these cultural differences are also psychological differences: from norms and attitudes, to the degree to which these norms are enforced, to low-level perception of color and visual illusions ( Boyd, 2017 Gelfand, 2019 Henrich, 2016). And even within WEIRD nations, there are psychologically relevant cultural differences ( Henrich et al., 2010 McCrae, Terracciano, & 79 Members of the Personality Profiles of Cultures Project, 2005). Nonetheless, the literature remains overwhelmingly WEIRD ( Rad, Martingano, & Ginges, 2018), and there exists no systematic method for determining which societies will provide useful comparisons or even the size of the psychological differences-the cultural distance-between societies, be they non-Western, less-educated, less-industrialized, poorer, nondemocratic, or some subset of these. Researchers often assess the generalizability of these findings by comparing Western nations with East Asian nations but are increasingly documenting differences in small-scale societies. Cultural distance predicts various psychological outcomes.ĭecades of psychological research designed to uncover truths about human psychology may have instead uncovered truths about a thin slice of our species-people who live in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) nations ( Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010).

Analyses of regional diversity reveal the relative homogeneity of the United States. Our code and accompanying online application allow for comparisons between any two countries. As the extreme WEIRDness of the literature begins to dissolve, our tool will become more useful for designing, planning, and justifying a wide range of comparative psychological projects. We applied the fixation index ( F ST), a meaningful statistic in evolutionary theory, to the World Values Survey of cultural beliefs and behaviors. We also present distance from China, the country with the largest population and second largest economy, which is a common cultural comparison. Because psychological data are dominated by samples drawn from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) nations, and overwhelmingly, the United States, we focused on distance from the United States.

In this article, we present a tool and a method for measuring the psychological and cultural distance between societies and creating a distance scale with any population as the point of comparison.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)